Prozac’s approval seeds by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1988 dawn a new era in the treatment of depression because they focused on serotonin, a chemical in the brain, when it is in a lack of supply, contributes to depression. It was more targeted and had less and less cruel side effects than classic remedies – exclusive oxidase inhibitors and mono -holy oxidase inhibitors (MAOIS).

since thenA total of seven selective serotonin absorption inhibitors (SSRIS), which mainly helps on nervous serotonin in accumulation in the brain by prohibiting its escape, hitting the market, as well as many serotonin and disturbance disorder. It is joined by medications such as Wellbutrin, which are not suitable for specific chemical categories.

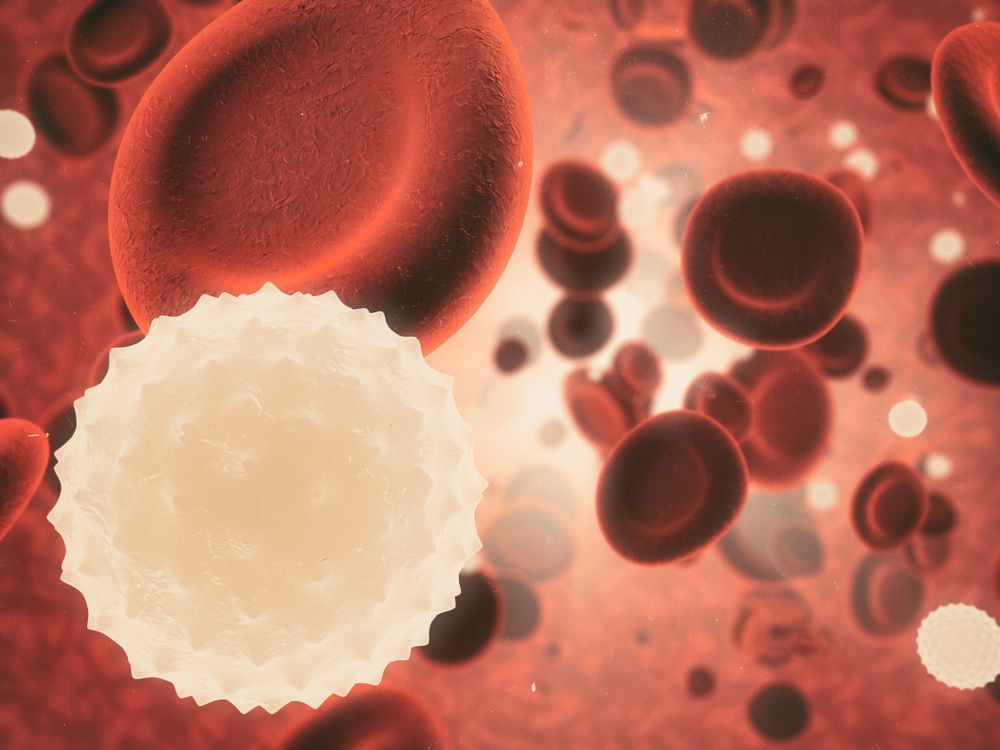

Some depression do not respond to medications. Scientists have assumed that inflammation – which seems to play a role in many aspects of our health, including our immune system and metabolism – may also contribute to depression as well as the condition of the treatment. Now, the scientists in Australia performed a work in mice that link how inflammation can disable metabolism, which makes the treatment of depression more challenging, it is a report In the magazine Brain, behavior and immunity. If it is repeated in humans, the research may help to match the medications better to patients.

Read more: What is inflammation, and why sometimes “bad” for your health?

Connect inflammation with depression

Even with reaching treatment, 10 percent to 30 percent of depression appears to be stubborn for the drug; Therefore, the treatment resistant depression (TRD) has been named. Exactly why this remained a medical mystery. Part of the problem is that the response to certain antidepressants – in terms of success as well as side effects – can vary greatly from the patient to the patient.

In mice, the researchers have investigated how to link the vital indicators associated with inflammation to dopamine – what Roger FarlalaQueensland University, Australia researcher and co -author of the paper, nervous carrier, “Feeling of Red”, ” In a press release.

Our brain feeds us as a reward for stimulating healthy behaviors. The study showed, in fact, that inflammation and metabolism can interfere with the dopamine factory in the brain. Then our brain bonus closes a store, which leads to symptoms of classic depression such as Anhedonia – the inability to try joy or pleasure. Continuous anhedonia is a sign of TRD or to treat depression that may be partially effective.

“This knowledge teaches our development of a blood test that can predict the potential response of a person to various antidepressants, which may simplify his diagnosis, improve his treatment and save time and health care,” Farla said in a press statement.

Read more: The treatment of the intestine, not the brain, can help depression and anxiety

Providing optimism to those who suffer from TRD

This study provides both short -term and long -term hope for those diagnosed with TRD. The short -term solution does not include any medication at all. The appropriate diet, exercise, and sleep can play a role in controlling inflammation, indirectly, helps in managing depression.

Long -term expectations are also positive. Although this is the pre -clinical work in animals, it does not include the development and test of a new drug for safety and effectiveness. This process can take decades. Instead, it provides a path forward to a blood test that can help doctors match one of the many drugs available to the patient based on the immune system and metabolic signs.

“If we can collect the patient’s vital file, we may be able to predict whether they will respond or not to certain antidepressants,” Varilla said.

This article does not provide medical advice and should be used for media purposes only.

condition sources

Our book is in DiscoverMagazine.com Use studies reviewed by peers and high -quality sources of our articles, and review our editors for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Before joining Discover, Paul Smaglik spent more than 20 years as a scientific journalist, specialized in American life sciences and international scientific job issues. He started his career in newspapers, but he turned into scientific journals. His work appeared in publications, including news of science, science, nature and scientific America.